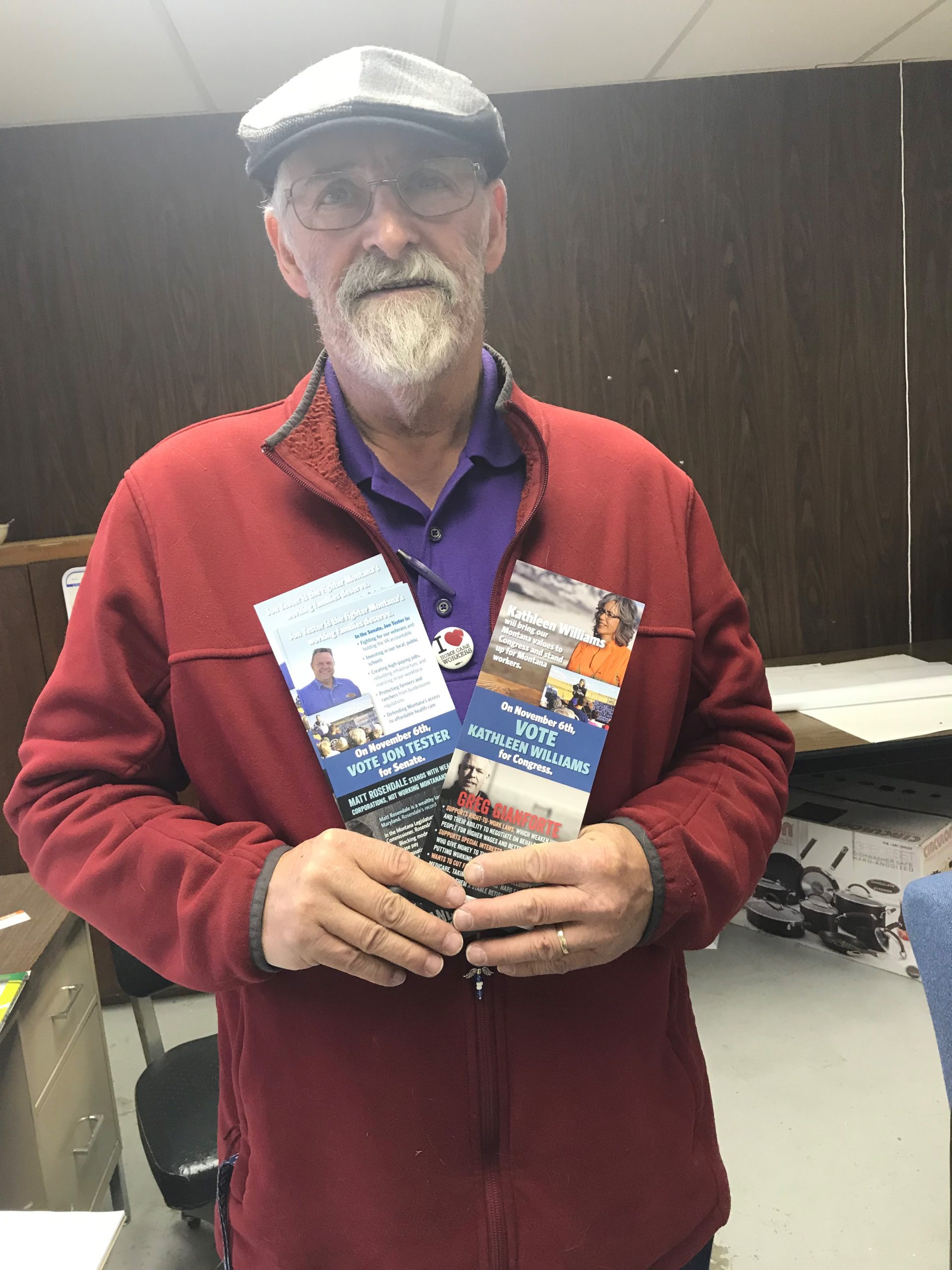

Montana Legislators,

We will talk about what we lived through in 2020 and 2021 for the rest of our lives. It was a year of incredible heartache and loss and sadness and loneliness.

But that’s not all the year was. It was a year when lawmakers and our residents showed up like never before and lifted up essential workers who were taking care of the people who are most vulnerable to this virus.

At the beginning of this pandemic, people across the country – including many of you – came together to clap for essential frontline workers like caregivers to show your appreciation for the hard work we do to help our communities. While the clapping has stopped, these essential workers are still hard at work.

That’s why we’re asking you: You Clapped. Now Act!

We need Agencies and Provider Rate increases not cuts because cutting long-term care funding in a pandemic is tantamount to neglect. Will you take action to support our frontline workers just like you did last year?

“The proposed cuts to the senior long term care budget are only going to make the next 2 years even harder. For my clients, they don’t get much help as it is now, and it would be a devastation if he lost any hours. For myself, it means that at 62, I would have to look for another job in order to make a living. Please oppose any cuts to the senior long term care budget.”

– Lori Swartz, Missoula, MT

“Support us the way we never fail to support you, your families, and our clients and communities.”

“I’m Lisa Jensen, and I’ve been a caregiver for almost 25 years now here in Montana. I currently work with medically frail clients who need complete care at a group home in Butte. I am writing today to remind you how much we need you to remember all of us always, but especially during this Montana Legislative Session.

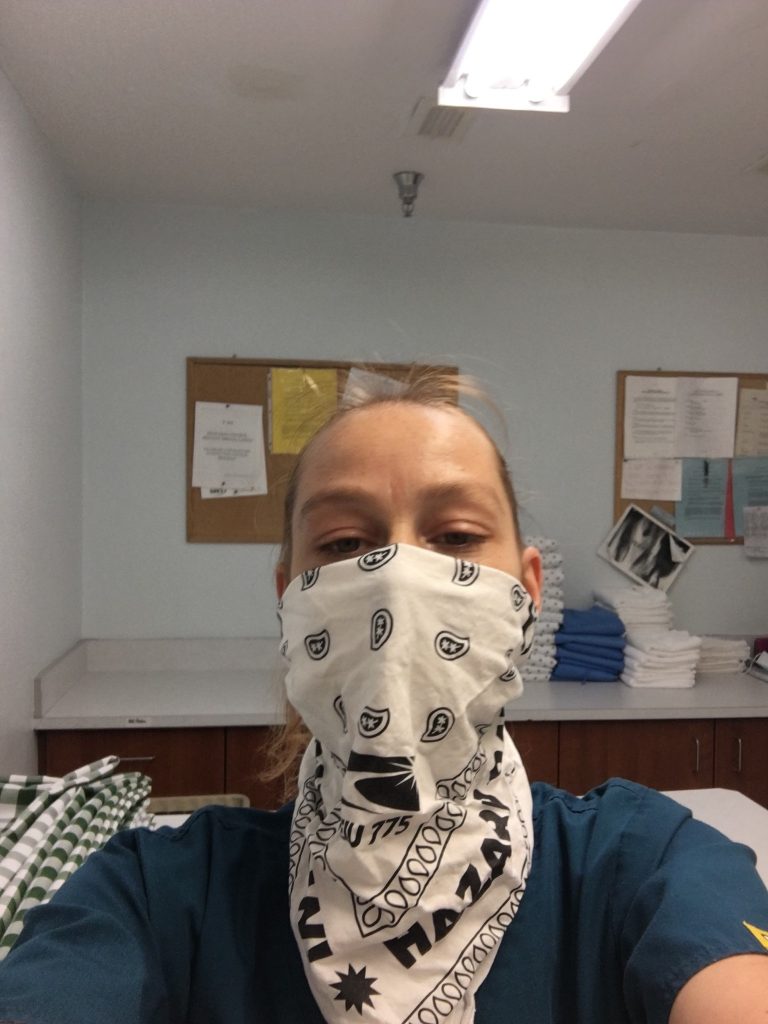

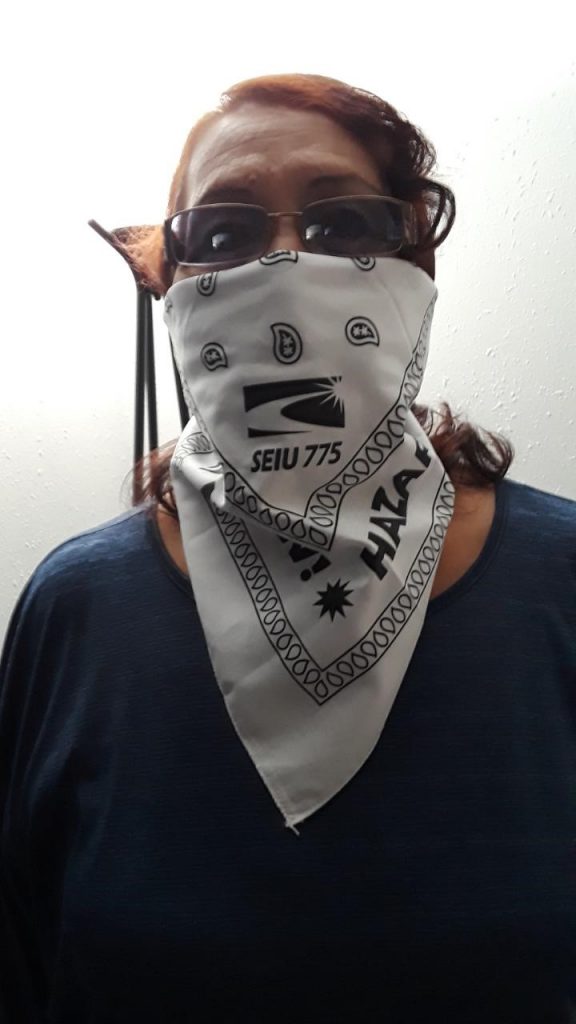

I love being a caregiver. Even so, I can tell you for sure that we do not make a fair, living wage for the important work we do. That has never been more true than during this pandemic. Way too many people think things like getting enough PPE, having access to hazard pay, and other things we as caregivers and our clients need is some kind of made-up joke. I am here to tell you it’s not.

We have had several positive Covid cases throughout my job’s network of group homes and other programs for our vulnerable clients all across Montana and also right here in Butte. If there are positive cases in our group homes, the staff there have to go into a two-week quarantine with their coworkers and clients to contain the spread of Covid and do our best do to keep everybody as safe as possible.

Yes. You read that right. Montana caregivers at our group homes quarantine for two weeks. They leave their families, pets, and lives for that long to stay at work 24/7 with clients that are often sick, scared and stressed out. Have you ever quarantined for two weeks at work? We have. And we’ve done it during the financial, health and other stresses of living through a pandemic. No matter what, caregivers ALWAYS show up.

Now, we need – we expect – all of you to show up for us. This isn’t about politics or what party you’re in. This is about the health and safety and lives of Montana caregivers, our families and our clients.

Please remember who you’re in Helena to serve and do the right things. We need true living wages and access to good healthcare now more than ever. This pandemic has proven just how essential we are. Support us the way we never fail to support you, your families, and our clients and communities.”

– Lisa Jensen, Butte, Montana

I need you to fight for our clients so they have the hours for their care and I can keep my job and a roof over my head. Please oppose any cuts to the senior long term care budget. We’ve come too far to see our wages roll back now.

Delphine Camarillo

Billings, MT

“We’re just now recovering from budget cuts in 2017.”

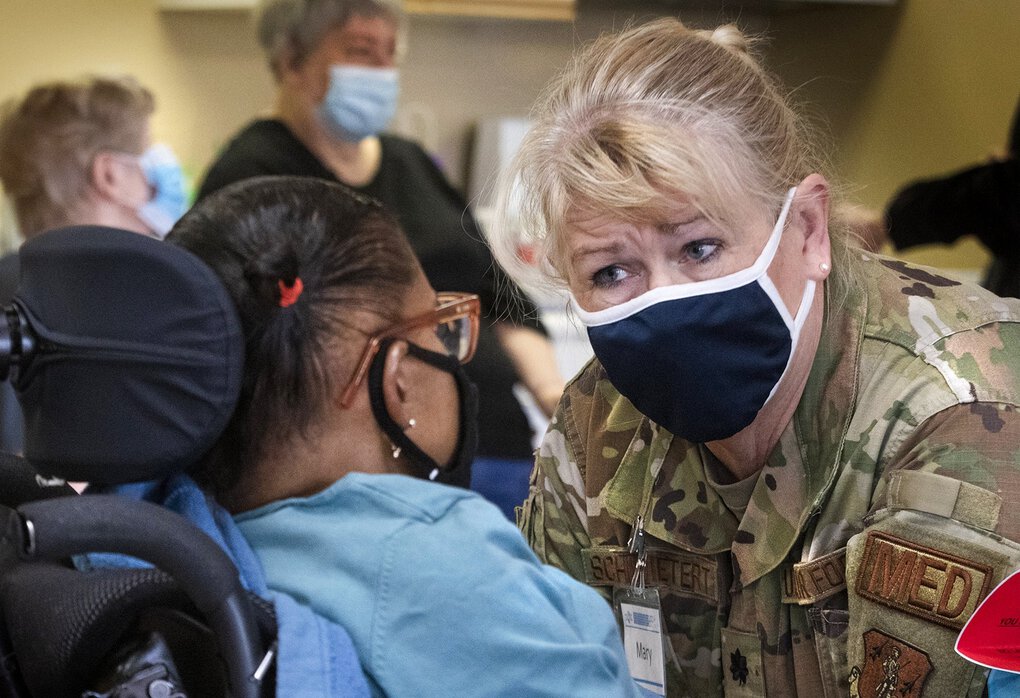

“Caregiving is a challenging occupation because of the physical, mental and emotional affects that come with the job. It’s physically hard because we are using our bodies as a physical assistance device in helping our clients with getting out of bed, toileting and any other mobility task. They are constantly leaning on us for support, or we are lifting them. It’s real easy to do it the wrong way and injuries are common especially as you get older. In my prime, I saw it as great exercise, but after 30 years the body breaks down and you heal a lot slower. One time I tweaked my back in my sleep, and had to use a walker for a month. The work is also mentally and emotionally stressful because we’re constantly afraid of losing hours. Most of us are still living paycheck to paycheck, and some months it feels like we’re just treading water. I’m doing the work of multiple professional people, but only paid a fraction of what they are worth.

COVID-19 has provided some unique challenges for caregivers. It’s hard for our clients to hear us clearly through our masks, and not being able to see our faces makes some of them uncomfortable. We’re doing it to protect them, but it creates a lot of anxiety because so much of communication is non-verbal. Sometimes they don’t recognize us, or they forget that we are in the middle of a pandemic and ask why we’re wearing a mask at all. I’ve lost relatives to COVID-19. I know the pandemic is real, but many of our clients just do not understand.

At the height of the pandemic, caregivers were praised as heroes, but more often than not we’re treated like we are a dime a dozen. Please don’t cut the funding for senior and long-term care. We’re just now recovering from budget cuts in 2017. That made life so much more difficult and we lost a lot of good caregivers that couldn’t make ends meet anymore. Budget cuts add stress to an already stressful job. When you cut our budget, it doesn’t decrease the amount of work we have to do, it just means we have less time to do it.”

– Connie Sharp, Glasgow, Montana

Most of our clients are poor and would be on the street if it weren’t for state funding. The budget cuts being proposed could be a matter of life and death for many of our clients.

In 2017, we faced severe cuts to our funding, and we just got that funding back in 2019. To turn around two years later and strip funding again is cruel and unfair. We work hard and live simply. Don’t take away our livelihood.

Celeste Thompson

Missoula, MT

“Budget cuts to a healthcare system already underfunded just cannot happen.”

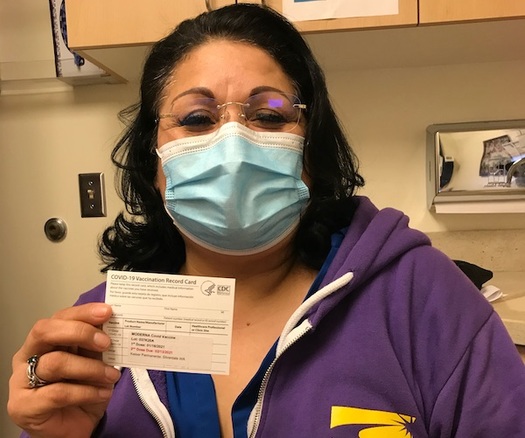

“I love being a caregiver. It’s who I am and the work I want to do. I strongly believe there cannot be any higher calling than upholding the dignity of our most vulnerable folks.

Over the last year, continuing to work through the pandemic has been an experience I had hoped to never have as a caregiver. My job is always stressful, sure. I often work 70-80 hours every week, not only because I care so much about my clients, but also just to try to make a living. Caregivers never make enough. Especially with the important, complex and challenging work we do. That is always true. That truth has never been more obvious than during the pandemic.

Even so, we all just keep showing up. Every day. No matter what. In fact, I was pretty sick this fall and my doctors were pretty sure it was Covid. I had a lot of the usual symptoms. The stress of having to face that was tremendous. First, I don’t have very good health insurance so going to the doctor is always a tough choice financially. But we are in the middle of a pandemic, so not knowing whether I had a virus that could kill me, my coworkers, or my clients, I had to go, figure out how to pay the deductibles and the copays, and find out. I even had to advocate strongly to even get access to a Covid test, since our healthcare system in Montana has struggled to keep enough PPE, testing and other necessary supplies available. I was very lucky. My test was negative. Thousands and thousands of other Montanans can’t say the same.

Budget cuts and other policy changes to a healthcare system already underfunded just cannot happen. I need you to remember me, other Montana caregivers, and our clients when you make these decisions.

Thank you for your time and consideration. Do not forget us.”

– Winter Maulding, Butte, Montana

We need more funding, not less. We need hazard pay through all of the pandemic, and we need and deserve higher, living wages after that. Do not forget about us. Me and my coworkers are taking care of your family members here in Libby. We deserve your help in taking care of our families, too.

Sharon Smith

Libby, MT

“I’ll lose hours one week, then get them back, only to lose them again the following week.”

“I’ve worked at nursing homes, in hospitals, and have been a caregiver in one former or another for 38 years. Basically, I go into people’s homes and help them with all the little things they need to live – bathing, cooking, house cleaning, laundry, oral care, and shopping. If you’ve never done this work, it’s not for the lazy or the faint of heart.

The biggest impact from the pandemic has been the loss of hours. It’s been a constant battle back and forth as clients are in and out of the hospital, or just afraid of having someone in their homes. I’ll lose hours one week, then get them back, only to lose them again the following week. You never know what to expect. I lost my health insurance over it at the end of last year.

It’s also hard on the people we care for because they are so limited in what they can do. It makes them mad. They don’t understand why we can’t just go to the park or the store like we’ve always done. It’s times like these that our work is even more important. We are their connection to the outside world.

I don’t know where the world is going these days. I try to have faith that things will work out, but it’s a struggle to stay positive. What keeps me going is the difference I make to my clients. I love helping people and bringing joy into their lives. Everyone deserves that, and they deserve to be treated with dignity and respect. I hope you will support this resolution and give all healthcare workers the respect that we have earned.”

– Audra Gairrett, Billings, Montana

When people think of front-line healthcare workers they usually think about doctors and nurses, but homecare workers are on the frontlines too. Every day, we work to keep our clients in their homes and out of the hospitals and nursing homes. Without our work, the healthcare system would be overwhelmed and conditions would be much worse right now.

In spite of our sacrifice, caregivers are some of the lowest-paid workers in our community. Our work happens behind closed doors, and we feel practically invisible.

Winnie Schafer

Wolf Point, MT